The Blue And The Gray

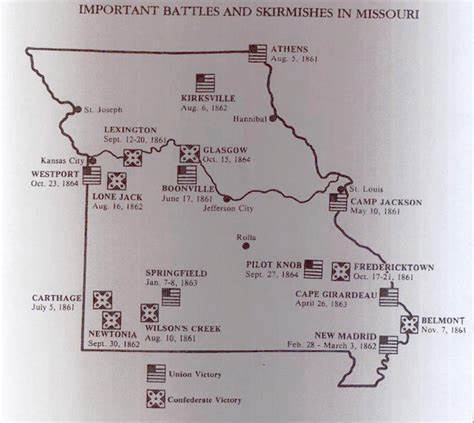

During the Civil War, Johnson County was the scene of harassing activity, for both the Blue and the Gray were organized to resist opposing forces. Some lives were lost through these guerilla activities, and much property was destroyed by lawless people who took advantage of the times.

Because of the insecurities of life and property, many of the best citizens left their homes and farms. These were often sold for ruinous prices, or even abandoned.

But with the end of hostilities, the energy of the people was re-awakened. The populace returned vigor, and soon prosperity had exceeded that of ante-bellum days.

From “The Golden Years 50th Anniversary Johnson County Historical Society 1920-1970”

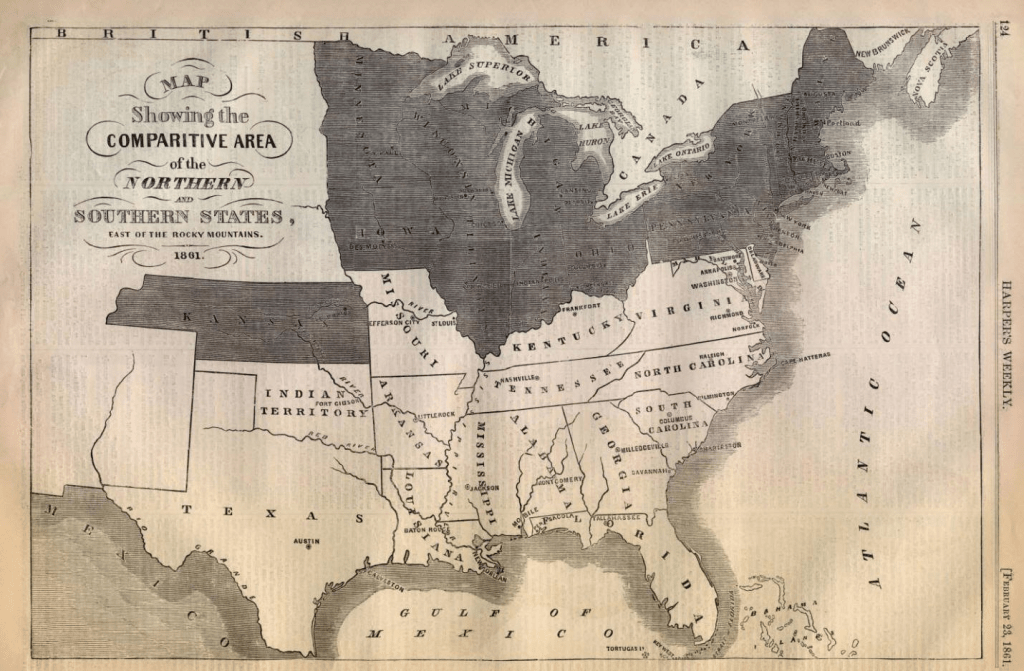

Johnson County, Missouri: A Divided Heartland at the Brink of War

In the years leading up to the Civil War, Johnson County, Missouri, stood at the crossroads of American conflict—its fields fertile with both crops and contention. Nestled along the Missouri River, the county was part of the nation’s “great slaveholding belt,” where Simpson Township alone had a majority of enslaved people. Yet, this land also attracted small farmers from East Tennessee, Kentucky, and the Carolinas—many of whom were staunch Whigs and Unionists opposed to slavery. This mix of ideologies created a volatile political climate, with Whigs and Democrats nearly evenly split.

The Whigs, often newcomers from the free states, were small-scale farmers and laborers who viewed slavery as both morally wrong and economically backward. In contrast, the Democrats were largely wealthy landowners and slaveholders from the South, including Virginia, Kentucky, and Georgia. Their influence was bolstered by social prestige and a strong pro-secession stance. Despite this, the Whigs and Unionists were a determined and numerous group, unwavering in their commitment to the Union cause.

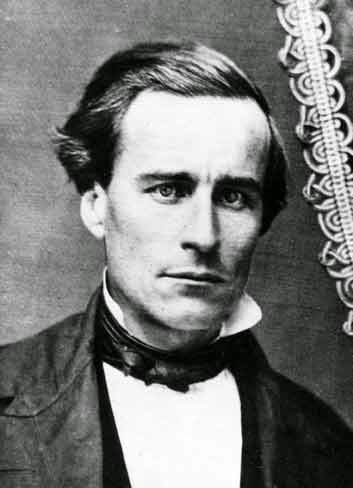

In 1861, the county made a decisive choice, electing Aikman Welch—a respected Missouri-born lawyer and Unionist—as a delegate to the state constitutional convention. Welch’s victory over secessionist M.C. Goodlett was a clear statement of Johnson County’s allegiance. Welch’s prominence grew quickly; he was appointed attorney-general but tragically died in office during the war.

Aikman Welch Appointed Missouri Attorney General After J. Proctor Knott’s Refusal to Take Loyalty Oath (1861)

In 1861, as Missouri grappled with its divided loyalties during the Civil War, J. Proctor Knott, the state’s Attorney General, refused to swear allegiance to the Union. His refusal led to his resignation and brief imprisonment. Provisional Governor Hamilton R. Gamble swiftly appointed Aikman Welch, a staunch Unionist and accomplished Missouri-born lawyer, to the position. Welch’s appointment marked a significant shift in the state’s legal leadership during a pivotal moment in American history.military-history.fandom.com+2library.blog.wku.edu+2en.wikipedia.org+2en.wikipedia.org

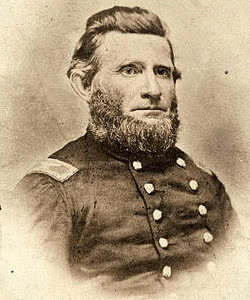

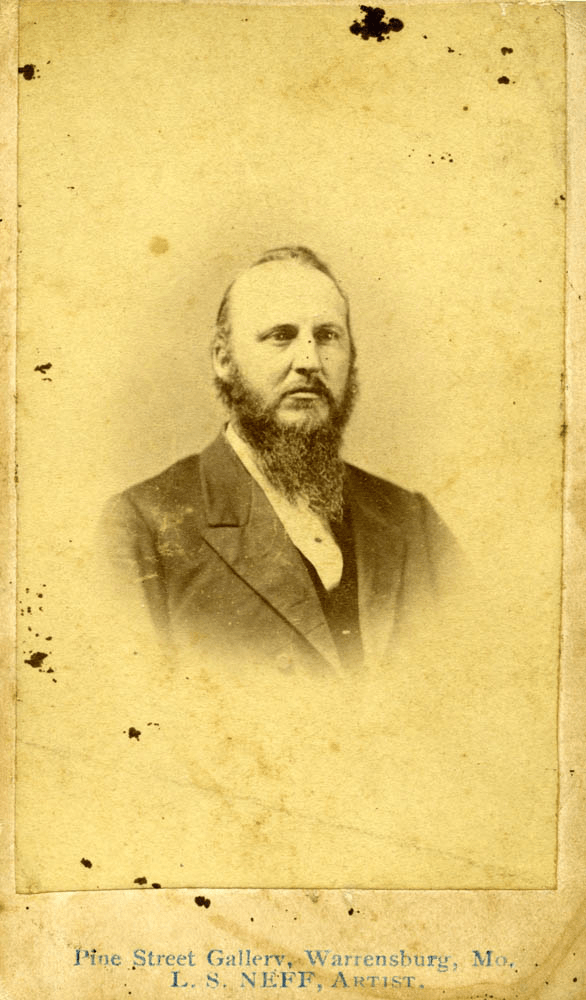

Among the leading Union figures in the county was Benjamin W. Grover, a native of Ohio who settled in Johnson County in 1844. A lifelong Whig and opponent of both slavery and secession, Grover was a former state senator and an early director of the Missouri Pacific Railroad. He played a pivotal role in Welch’s election and, as tensions escalated, publicly declared his intention to join the Union army at the first opportunity. Grover’s leadership was instrumental in organizing Unionist forces in the county.

Col. Benjamin W. Grover 1811-1861

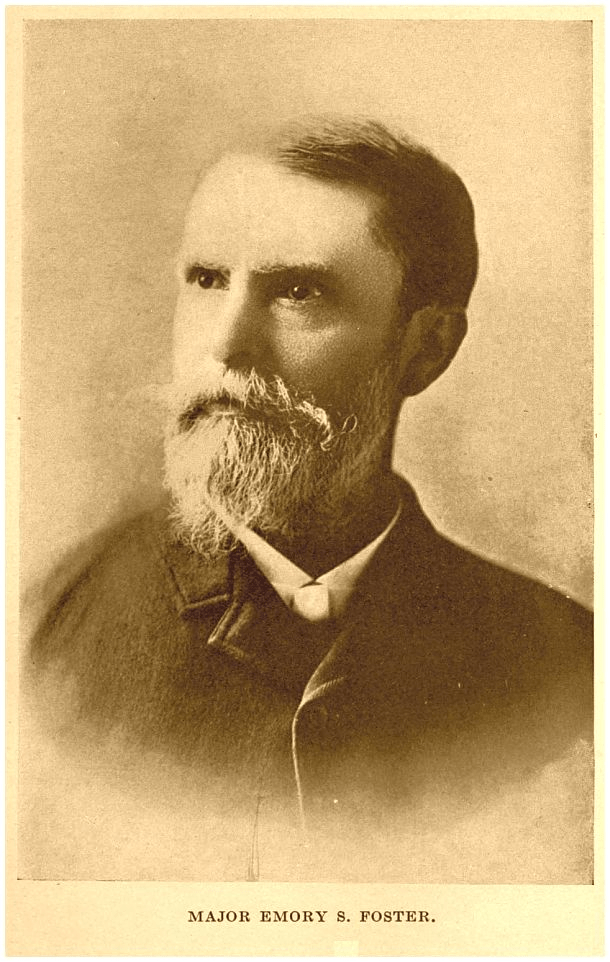

The assassination of Marsh Foster, a prominent Unionist and the son of Robert A. Foster, a Southern Methodist minister and Union supporter, marked a turning point. On February 18, 1861, Foster was killed at the county courthouse in Warrensburg by James and William McCown, a father and son duo with strong secessionist sympathies. The murder occurred on election day, just as the nation was on the brink of war. Marsh Foster’s death galvanized the Unionist community. His brother, Emory S. Foster, formed a Unionist militia company known as “Foster’s Mounted Rangers” and later served as a major in the 7th Missouri State Militia Cavalry. Emory’s leadership was crucial in organizing local resistance against Confederate forces.

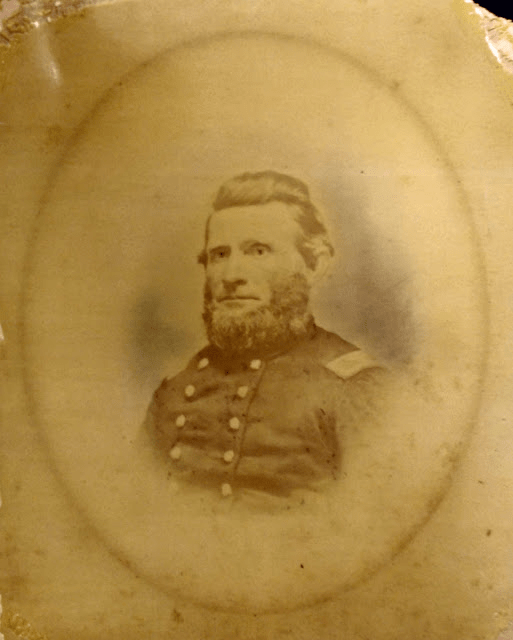

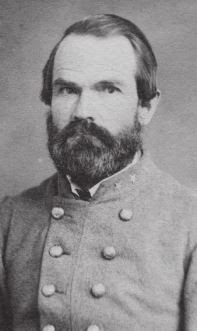

Colonel James Madison McCown

Colonel James Madison McCown was a prominent Confederate officer during the American Civil War. Born on March 21, 1817, in Virginia, he moved to Missouri in 1840 and became an influential figure in Warrensburg, serving as the county clerk and engaging in various community affairs. With the onset of the Civil War, McCown aligned with the Confederate cause, joining the Missouri State Guard. He rose to the rank of colonel in the 2nd Cavalry Regiment of the 8th Division. Following the dissolution of the Missouri State Guard, he continued his service in the Confederate Army, commanding the 5th Missouri Infantry Regiment. Under his leadership, the regiment participated in significant battles, including Iuka, Corinth, Port Gibson, Champion Hill, and Big Black River. After being captured during the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863, McCown was exchanged and led a consolidated regiment in subsequent campaigns, such as the Atlanta Campaign and the Battle of Fort Blakeley. He passed away on July 8, 1867, in Warrensburg, Missouri. en.wikipedia.org+4en.wikipedia.org+4kids.kiddle.co+4civilwartalk.com+5civilwartalk.com+5kids.kiddle.co+5en.wikipedia.org

In the aftermath of the assassination, the McCowns sought refuge in the county jail to avoid a lynch mob. Their lives were spared by the intervention of Grover and Emory S. Foster, who persuaded the crowd to allow the legal process to take its course. However, a grand jury composed of secessionists later refused to indict the McCowns, further inflaming Unionist sentiments. Both James and William McCown eventually served in the Confederate army, though their service was marked by controversy and lack of distinction.

And more than 20 years later, Billy “William” McCown was murdered, as further retaliation of Marsh Foster’s murder. The son was later found to be the one shooting Foster to death.

J Simmons 2023

The Red Shirt Company: Warrensburg’s Union Stand in 1861

In early 1861, as the nation teetered on the brink of civil war, the town of Warrensburg, Missouri, became a flashpoint for divided loyalties. Amidst this turmoil, a group of determined Unionists formed an independent military company, setting the stage for a unique chapter in local history.

Formation of the Red Shirt Company

Emory S. Foster, a staunch Union supporter and editor of the Warrensburg Missourian, took the lead in organizing the company. Joining him was T.W. Houts, who served as the first lieutenant. With military uniforms scarce, the men adopted a distinctive attire of red shirts and black pants, earning them the moniker “Red Shirt Company.” Their formation was not just a military endeavor but a bold statement of allegiance to the Union cause.

Securing State Arms

At the time, the Johnson County courthouse housed 100 state-issued muskets, intended for militia use under the 1857 Missouri militia law. However, secessionist sympathizers had hoped to seize these weapons for Confederate purposes. Foster and his company thwarted their plans by taking control of the arms, ensuring they were fully loaded and ready for defense. When authorities demanded their return, Foster stood firm, ultimately transferring the muskets to Colonel Benjamin W. Grover, who utilized them to arm his regiment .

Drills Amidst Division

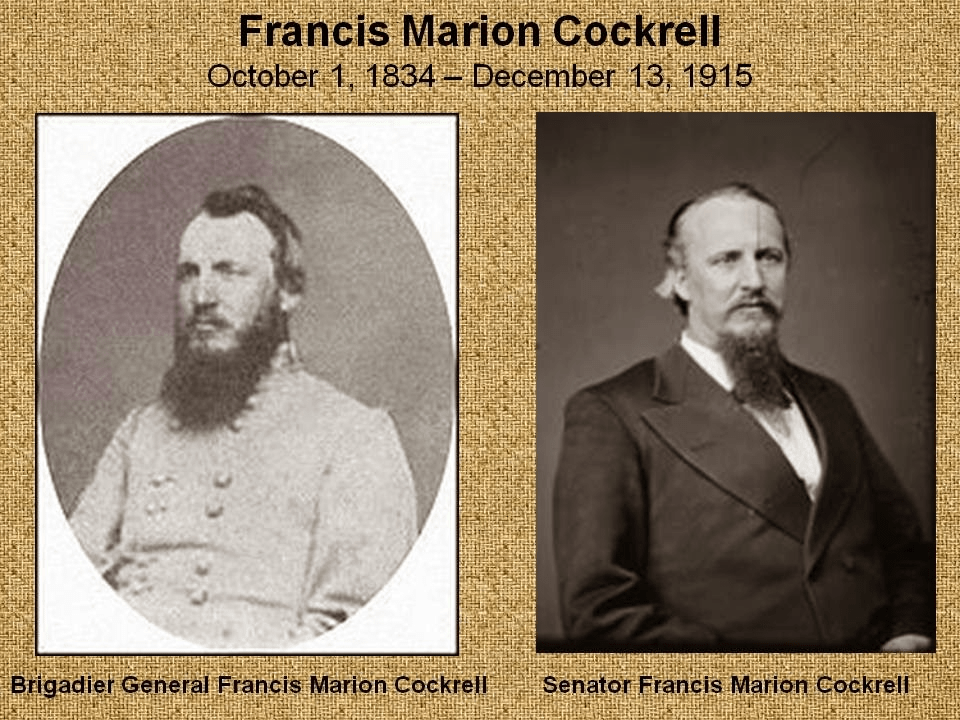

During this period, Francis M. Cockrell, a future Confederate general and U.S. senator, was recruiting for the Confederate cause in Warrensburg. Remarkably, Foster’s Union company and Cockrell’s Confederate recruits drilled on opposite sides of town. On several occasions, they even practiced together, exemplifying a rare moment of camaraderie amidst the nation’s deepening divisions

Opposition to the Harris Military Bill

The Missouri legislature, dominated by secessionists, passed the Harris Military Bill, aiming to raise a Confederate-aligned army. In response, B.W. Grover, a prominent Union leader, collaborated with Captain James D. Eads, a Democratic editor and veteran, to campaign against the bill in Johnson County. Their efforts galvanized Union sentiment in the region, leading to a decisive rejection of the conscription law.

Legacy of the Red Shirt Company

The Red Shirt Company, though short-lived, played a pivotal role in asserting Union loyalty in a divided community. Their actions not only secured vital resources for the Union cause but also fostered a spirit of unity and determination that would resonate throughout the Civil War era. Their story remains a testament to the courage and conviction of those who stood firm in the face of division.

The events in Johnson County were emblematic of the broader national conflict, where political allegiances, economic interests, and social divisions collided with deadly consequences. The county’s experience underscores the complex and often painful choices faced by border communities during the Civil War era. Johnson County’s legacy is a testament to the resilience and determination of those who stood firm in their commitment to the Union, even in the face of profound adversity.

J, Simmons 2023

From the W.L. Truman memoir

W,L, Truman

We passed through Warrensburg in Johnson County and thence to Clinton and on the Osage river in Henry Co. It seemed as if Harris’ Division had ten thousand men in it, all cavalry, and many of them without arms and without being sworn in to any command. This showed how loose and imperfect we were organized at the beginning. Gen. Martin E. Green’s Brigade, brought up the rear of this Southern movement and on the third day out from Lexington. My command would meet every morning as we left camp, men in squads of two to ten, going back, which showed a fearful want of organization and discipline. Men stayed with their friends and neighbors in the camp and on the march for days and weeks without joining the command or company; and then take their leave, several hundred at least went back before the army got out of Johnson County. I noticed how imperfectly our Quartermaster and Commisary departments were organized.

On the first day of our retreat, after marching all night we halted on the morning of Sept. 28th, 1861, about 8 o’clock to cook breakfast and feed our teams. We were issued rations from the captured stores and received other things as coffee and sugar. There were eight or ten men in my mess and one would go and draw rations for his mess of eight men, and then another would go and do the same thing until we got ashamed of ourselves, an quit. Our supply of sugar being so abundant, we not only used it for our coffee, but sweetened out water, and used it extravigantly on our bread. After an hour or two, our retreat was continued until late at night; we moved in a steady slow walk, through a prairie country, no timber except on the creeks. We did not go into camp in regular order, simply bivouaced in columns of four, as we were marching right on the road side and often in a lane. The fencing made of rails enclosing fine fields off all wheat and with the corn in the shock. We would go in and help ourselves to the corn and feed our horses, and often saw the rails burnt at night, as it was cold. We had but a single blanket.

On Sept. 29th we traveled about twenty miles, through some rain and bivouaced just where we halted on the roadside. We were now in Johnson County. On the 30th we resumed our march early and traveled about fifteen or twenty miles. We have had several hard rains today. We are still in Johnson County; halted for the night, right in a long muddy lane. Have no wood except fence rails. It is very distressing to me, to see the fencing burned from around the fields of corn and wheat, and so far from timber. It cost great labor and time and expense to fence these fields. It seems to be no hope of getting it replaced in time to save the fine crops of wheat. Doubtless the Northern army will pass this way and clean up what we have left.

. On Oct 1st, we started early, and had a bright fine day, saw nothing but prairie. It is rolling and beautiful and very rich. Some farms are in a high state of cultivation. I saw a fine-looking man riding down the line this evening, dressed in grey citizens clothes. His fine portly figure and intelligent appearance impressed me very much. I said to myself, “that must be Gen. Price,” and so it proved to be. He is truly a noble looking man and he has proved himself to be a great General..

Oct. 2st, 3rd, 4th. Continued our backward movement slowly through Johnson County, passed through Warrensburg and Rose Hill, in Henry County, and rested a day at Pappinsville.

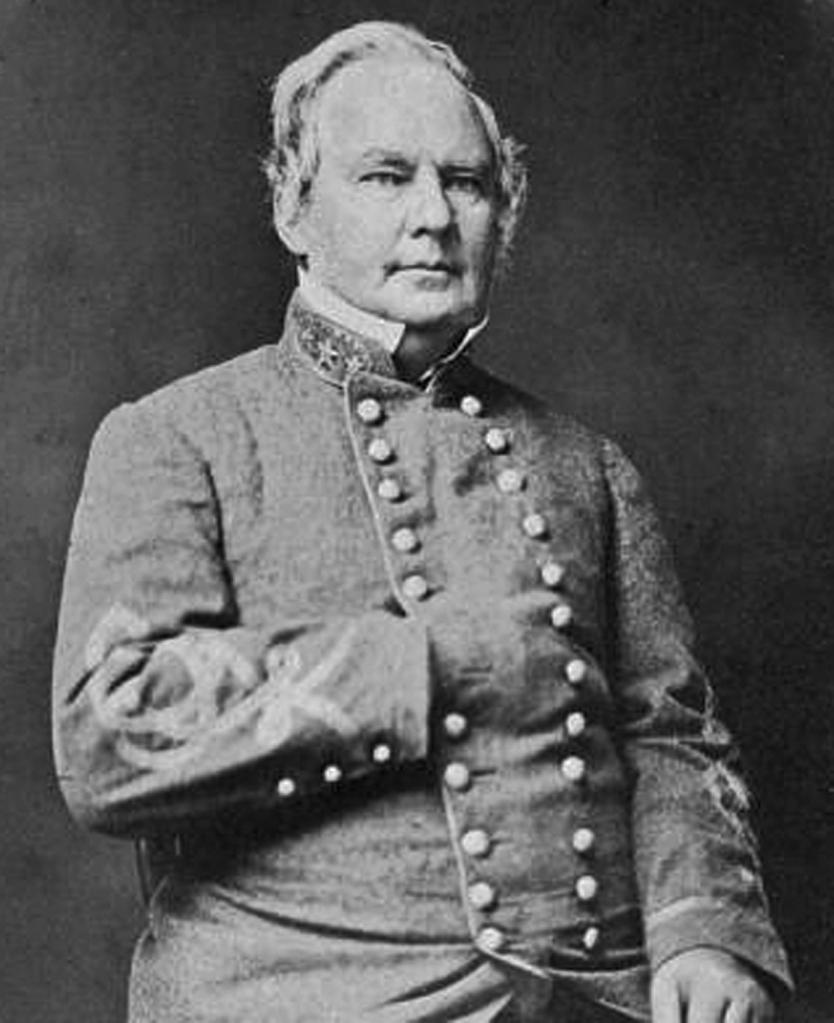

General Sterling Price

In the summer of 1861, as the nation teetered on the brink of civil war, Major General Sterling Price led the Missouri State Guard from Warrensburg to Lexington, marking a pivotal moment in the state’s tumultuous history.

Price, a former governor and seasoned military leader, had initially opposed secession. However, the Union’s seizure of Camp Jackson in St. Louis in May 1861, which resulted in civilian casualties, galvanized his shift in allegiance. By June, he had taken command of the Missouri State Guard, a militia formed to defend the state’s rights against federal encroachment.civilwarvirtualmuseum.org

Departing from Warrensburg, Price’s forces, numbering approximately 12,000, advanced northward. Their objective was Lexington, a strategically significant town along the Missouri River. Colonel James A. Mulligan commanded the Union garrison there, comprising about 3,500 soldiers, including contingents from Missouri, Kansas, and Iowa. Despite being outnumbered and underprepared, Mulligan was determined to hold the town.

On September 12, 1861, Price’s advance elements arrived at Lexington, initiating a siege that would last several days. Mulligan’s forces constructed formidable earthworks and prepared for a protracted defense. However, the Confederate artillery proved overwhelming, and on September 20, Mulligan was compelled to surrender. The capture of Lexington was a significant Confederate victory, bolstering morale and solidifying Price’s reputation as a capable commander.

On March 26, 1862, Col. William Quantrill and a band of over 200 Confederate raiders entered the town of Warrensburg that afternoon. Their objective was a Union outpost in the town. Warrensburg was commanded by Maj. Emory Foster and a detachment of 60 soldiers of the 7th Missouri Cavalry. Foster had fortified the brick county courthouse and had his men posted behind a thick board stockade surrounding the building. The Confederates made a failed charge against the Federals and was driven off at dusk.

Francis Marion Cockrell was born October 1, 1834, near Warrensburg, Missouri; he graduated from Chapel Hill College in 1853, and became a lawyer in 1855. With the start of the Civil War, Cockrell raised a company for the Missouri State Guard and fought at Carthage and Wilson’s Creek. Early in 1862, he transferred to Confederate service and participated in the Battle of Pea Ridge.

Cockrell led the First Missouri Brigade during the Vicksburg campaign, was wounded in the hand during the siege of that city and was captured when Vicksburg fell. Promoted to brigadier general on July 23, 1863, while a prisoner, he was exchanged that September. Cockrell formed another brigade of Missourians at Demopolis, Alabama, and led them through the Atlanta campaign. He was seriously wounded at the 1864 Battle of Franklin, but recovered and joined his command at Fort Blakely, guarding land access to Mobile. When the fort fell to Union forces on April 9, 1865, Cockrell was captured with 1,300 other Confederates.

After the war, Cockrell returned to Missouri and practiced law. In 1874 he was elected to the United States Senate, where he served thirty years. In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Cockrell to the Interstate Commerce Commission, a position he held for five years.

Cockrell died in Washington, D. C., on December 13, 1915, and is buried in Warrensburg, Missouri.

Carte-de-Visite by L.S. Neff, Warrensburg, Mo.

Image Courtesy Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield; WICR 31540

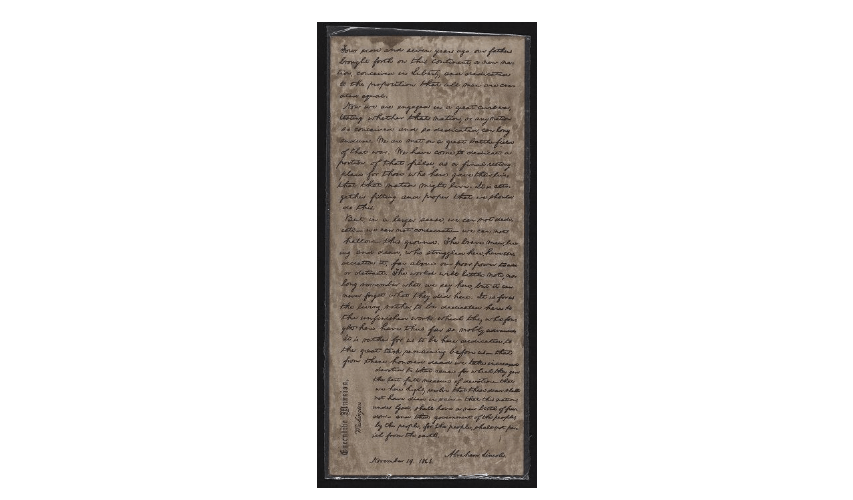

This is a facsimile of President Lincoln’s handwritten copy of the Gettysburg Address. Lincoln delivered the famous speech on November 19, 1863 at the Soldiers National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. In his address, Lincoln memorializes the Battle of Gettysburg and declares that the Declaration of Independence guarantees the liberty and equality of all people. He concludes by proclaiming that the “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.